Regensburg is a lively World Heritage site on the River Danube. Viewed from the stone bridge (built ca 1135), the Cathedral of St. Peter rises above the town skyline. Below the spires, white umbrellas mark the Wurstkuchl which has been selling bratwurst for over 500 years.

Construction on the cathedral began in 1273 and follows a high gothic design established by the second architect in 1285. The design was adhered to through completion in 1872. Thus the church has a remarkably coherent appearance for its 600 year timeline.

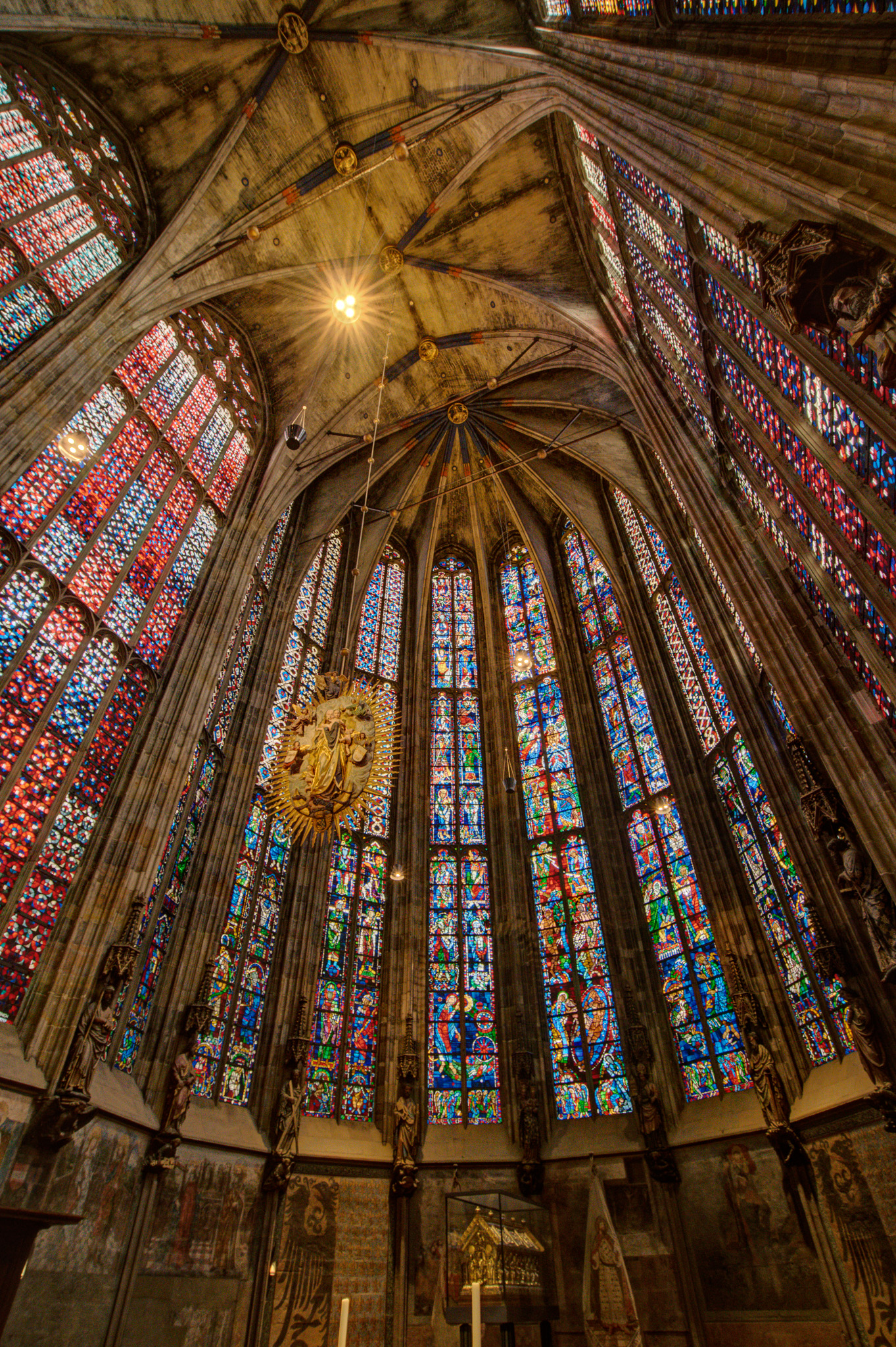

Originally, the interior was painted and frescoed. Elaborate ornamentation was added during the Baroque era. In the 19th century the decorations were removed leaving only the stone with the vertical lines of the columns leading the eye upward, while the early gothic windows and silver altar (19th century) draw the eye forward. Light from the aisle windows alternates with shadows to give dynamism to the entire interior.

Although Germany is largely a secular nation, many still seek spiritual connections. A few folks can be often be found in quiet prayer or meditation, especially in the morning before most tourists arrive.

The organ in the north transept was installed in 2009. It is suspended by four cables that pass through the vault and connect to a steel structure above. The sculpture of Mary in the lower left faces the angel above the praying man in the previous image. Together they represent the annunciation and were carved about 1280/85.

Unlike the churches of the Rhine which are build mostly of red sandstone, Regensburg Cathedral is constructed primarily of limestone. There are however many places where green sandstone was used. The sandstone is soft and much eroded. I asked a couple official looking people about it but could not determine if both type of stone were original or if the mix was the result of prior renovations. If anyone can clarify, please leave a comment. Below is a close-up of the two types of stone.

Back on the bridge, as the sun was setting, a busker entertained passersby with music and bubbles.